the unsung pop revolutionary

The most influential record label you’ve never heard of

In 1962, Bill Wellings had an idea that would change the course of the record industry for decades to come.

An ad-man at London's J Walter Thompson, he had no particular musical talent, no contacts in the music business and no experience of making or selling records. But he'd had enough of writing ads to sell other people's crappy products, and he was pretty sure his idea had legs.

He picked the brains of management and sound techs at London's most venerable recording studios to find the country's top session musicians, singers and arrangers. Then he booked as much studio time as his limited funds would allow (overnight sessions were the cheapest) to record ‘soundalike’ versions of the biggest selling hits of the day. He packaged them up into compilations and pressed them onto a 7" EP, allowing him to sell six tracks for the price of one 7" single.

Sounds simple enough, but he'd effectively invented two new categories of product – the compilation album and the budget record. Quietly and without much fanfare, Bill Wellings made pop music affordable to teenage fans, most of whom had been priced out of the singles market until then.

In doing so, he made one of the most significant contributions of any record producer to the birth of teen culture that would sweep the world and dominate the pop music scene right up to the present day.

The first record featured covers of Cliff Richard’s Summer Holiday, Ronnie Carroll’s Say Wonderful Things (the UK’s 1963 Eurovision entry), Suki Yaki by Kyu Sakamoto (you may never have heard of it, but in 1963 it was a global sensation, selling more than 13 million copies), and a rousing arrangement of Hava Nagila!

Despite astonishingly fast turnaround times, Bill maintained relentlessly high production values, earning him a reputation for quality and professionalism that more than matched some of his big-name contemporaries.

But the record industry is a tough nut to crack, and even in the wild years of the early 60s it was hard for a newcomer to get a toehold.

With no distribution or record label tie-up, Bill famously sold the first two pressings from the boot of his car, driving up and down the country between recording sessions, sweet talking newsagents and bookshops to take a few dozen units off his hands.

With a wife and two young kids to support, the effort nearly broke him. At one point, cash flow was so tight he was dodging the bailiffs.

But eventually the creativity, technical perfectionism and hard work paid off. By the end of 1963, he'd signed deals to supply national chains like Woolworths and WH Smith and Top 6 was selling 100,000 units a month. The record industry started paying attention and in February 1964 Bill signed a distribution deal with Pye Records, whose studios he was using to record his tracks.

Shortly after that, he started work on an LP compilation series under an agreement with Music for Pleasure, a joint venture between EMI and book publisher Paul Hamlyn.

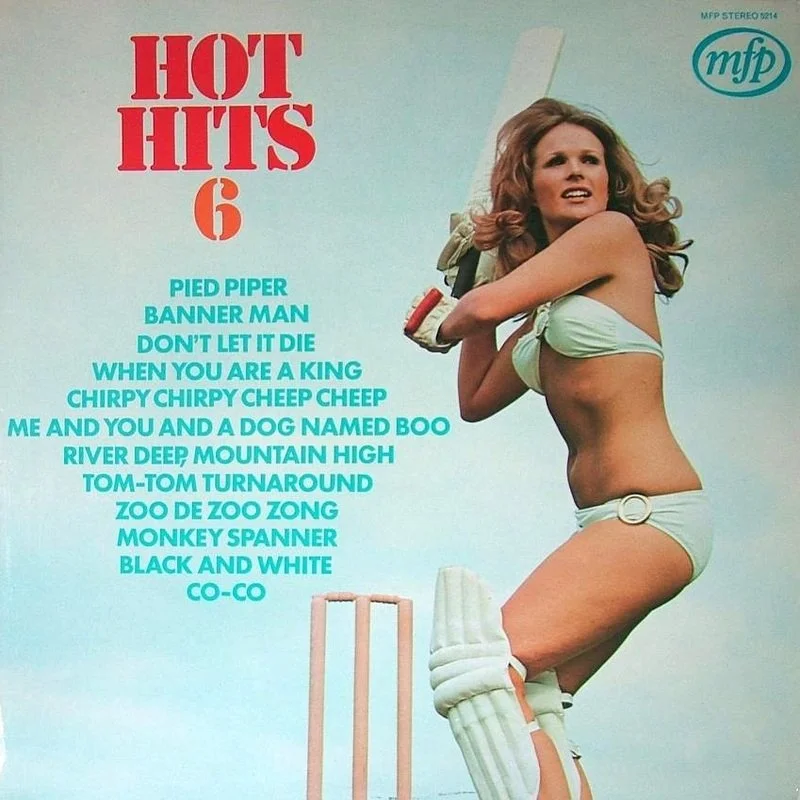

This was to become the legendary Hot Hits series. Millions who grew up in the 70s will remember these albums fondly, with their cover art featuring cover girls in sporting scenarios.

For the first couple of years, the UK Charts Company excluded BWD records from the album charts, believing that price-based competition was unhelpful to industry interests. But in 1972 they relented, and Hot Hits 6 went in straight at Number One. Hot Hits 7, 8 and 9 all went into the Top Ten, after which the charts company went back to excluding them.

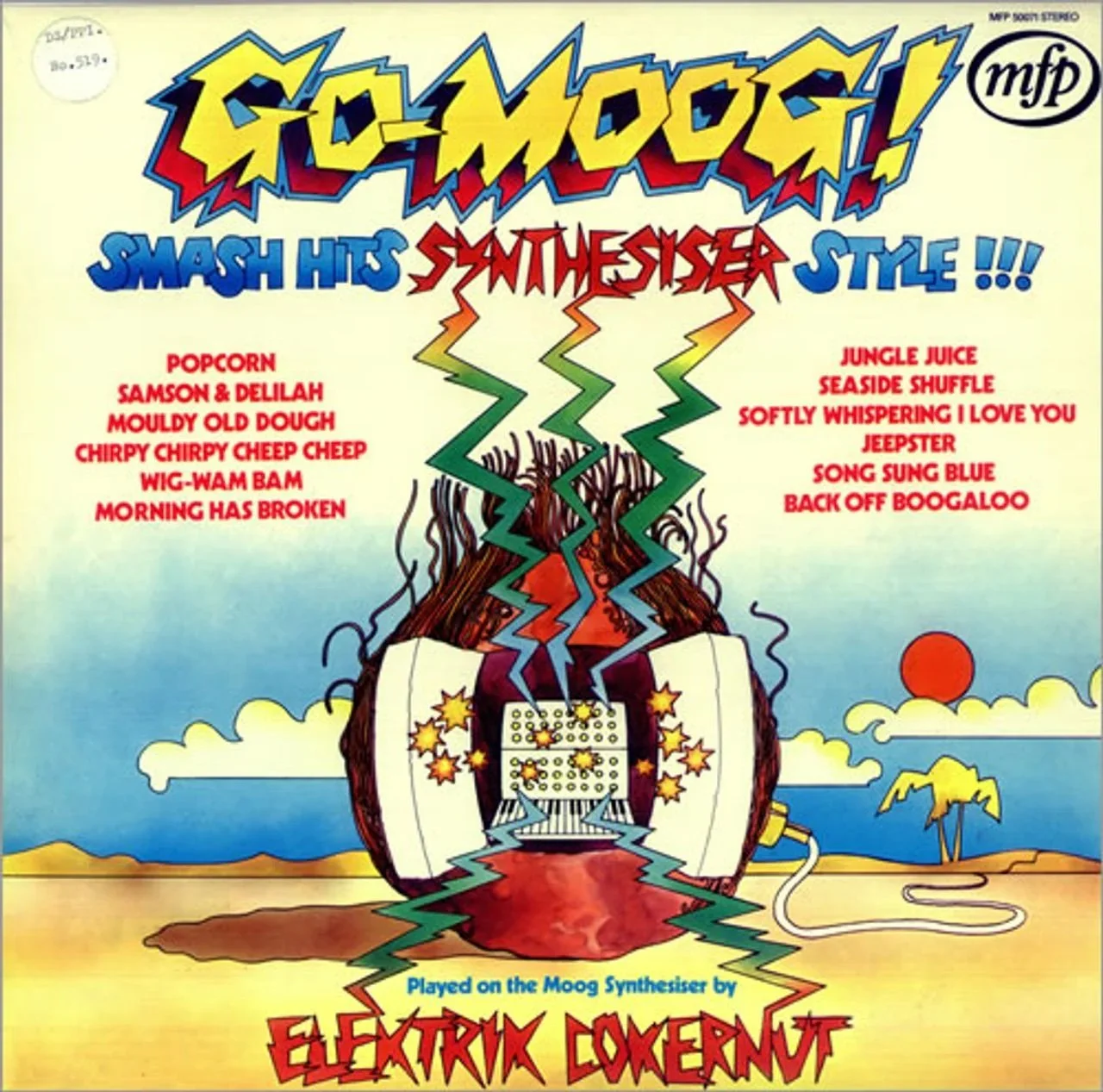

BWD branched out into other genres – film and TV themes and show tunes were big sellers. With his friend and collaborator Len Hunter, a fine musical arranger, Bill formed Elektrik Cokernut to record one of the world's first albums of electronic synth pop – Go Moog! Among the synth covers of classic and contemporary hits, the album featured a couple of original compositions by Len and Bill. One of them, a driving proto-jungle romp called Jungle Juice, would be sampled nearly 40 years later by Christina Aguilera on her album track I Hate Boys.

For some, he was little more than a knock-off artist: a forger boshing out cheap imitations of important works of art for sale to gullible consumers. But as far as Bill was concerned, anyone who thought a pop song was an “important work of art” was an insufferable twat.

He'’d grown up in the Great Depression and lived through World War Two – serving in the navy for the last 18 months of conflict. For him, pop music was an expression of joy and liberation. It was democratic, transcending class, gender and nationality. That’s why authoritarian regimes hated it so much.

The duo had fun with the classical canon too, reimagining Beethoven, Mozart and Brahms as jazz troubadours and kings of swing. The Bossa Nova rendition of Air on a G String was universally acknowledged as a musical masterpiece. Their Tijuana Christmas collection in 1969 was not only one of the world's cheesiest albums, but also Europe's top selling Christmas LP.

Over fifteen years, Bill and his travelling band of studio pros recorded over 2,000 tracks, many of which are still selling today.

But Bill Wellings was not the Che Guevara of pop. He was a businessman, and pop music is first and foremost a business.

Bill’s innovation was to recognise early on that not all fans of pop music were religious devotees of the bands and singers that performed it. Some of them – millions as it turned out – just loved the music.

For them, BWD came up with the goods, and a generation of teenagers have Bill to thank for endless hours of mooning about in their bedrooms, singing along to their favourite hits.

But all good things must come to an end, and by 1975, demand for budget covers albums was beginning to wane, exacerbated by the introduction of compilations from K-Tel and Now That’s What I Call Music, which featured original artist recordings at discount prices.

But Bill was already half-way out the door. Ten years is a long time to be cooped up in recording studios. And besides, he was about to enter his fifties and pop music is a young person’s game. There was, he felt, something faintly ridiculous and a bit sad about middle-aged music biz holdovers.

So in 1976, Bill Wellings called time on his career as a record producer. He sold the business and his house in the Surrey countryside, his boat in Monte Carlo, his Rolls Royce and assorted other cars and boarded an ocean liner to Brazil, where he underwent gender reassignment surgery and changed his name to Molly.

Not much is known of Molly’s life after 1980. It’s said she enjoyed some success in the theatre, which led to a brief romantic entanglement with a married cabinet minister in Margaret Thatcher’s government – one of the earliest examples of sleaze that would later define the Conservative Party.

She lived out her final days in a suite at the Savoy Hotel and passed away in December 2010, leaving behind an unpaid bill believed to run close to £150,000.

If true, it would be hard to imagine a more fitting end to one of the music industry’s great revolutions.